by Dr. Jaydeep T. Vagh

this topic discusses different computer components including buses,

the chipset, main memory, graphics and expansion cards, and the

motherboard; BIOS; the memory hierarchy; and how all these interact

with the microprocessor.

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Understand how the processor, chipset, and motherboard work

together. - Understand the importance of bus standards and their characteristics.

- Be aware of the differences between common bus standards.

- Describe the advantages and options when using a chipset.

- Describe the operation of synchronous DRAM.

- Describe the operation of a video adapter.

- Explain the purpose of BIOS.

- Calculate how memory hierarchy improves performance.

INTRO

A microprocessor can’t do anything by itself. What makes a processor

useful is the ability to input instructions and data and to output results,

but to do this a processor must work together with other components.

Before beginning to design a processor, we must consider what other

components are needed to create a finished product and how these com-

ponents will communicate with the processor. There must be a main

memory store that will hold instructions and data as well as results

while the computer is running. Permanent storage will require a hard

drive or other nonvolatile memory. Getting data into the system requires

input devices like a keyboard, mouse, disk drives, or other peripherals.

Getting results out of the system requires output devices like a monitor,

audio output, or printer.

The list of available components is always changing, so most proces-

sors rely on a chipset of two or more separate computer chips to manage

communications between the processor and other components. Different

chipsets can allow the same processor to work with very different com-

ponents to make a very different product. The motherboard is the cir-

cuit board that physically connects the components. Much of the

performance difference between computers is a result of differences in

processors, but without the right chipset or motherboard, the processor

may become starved for data and performance limited by other computer

components.

The chipset and motherboard are crucial to performance and are

typically the only components designed specifically for a particular

processor or family of processors. All the other components are

designed independently of the processor as long as they communicate

by one of the bus standards supported by the chipset and motherboard.

For this reason, this chapter leaves out many details about the imple-

mentation of the components. Hard drives, CD drives, computer printers,

and other peripherals are complex systems in their own right (many

of which use their own processors), but from the perspective of the

main processor all that matters is what bus standards are used to

communicate.

Bus Standards

Most computer components are concerned with storing data or moving

that data into or out of the microprocessor. The movement of data within

the computer is accomplished by a series of buses. A bus is simply a col-

lection of wires connecting two or more chips. Two chips must support

the same bus standard to communicate successfully. Bus standards

include both physical and electrical specifications.

The physical specification includes how many wires are in the bus, the

maximum length of the wires, and the physical connections to the bus.

Using more physical wires makes it possible to transmit more data in

parallel but also makes the bus more expensive. Current bus standards

use as few as 1 and as many as 128 wires to transmit data. In addition

to wires for data, each bus standard may include additional wires to

carry control signals, power supply, or to act as shields from electrical

noise. Allowing physically long wires makes it easier to connect periph-

erals, especially ones that might be outside the computer case, but ulti-

mately long wires mean long latency and reduced performance. Some

buses are point-to-point buses connecting exactly two chips. These are

sometimes called ports rather than buses. Other buses are designed to

be multidrop, meaning that more than two chips communicate over the

same set of wires. Allowing multiple chips to share one physical bus

greatly reduces the number of separate buses required by the system,

but greatly complicates the signaling on those buses.

The electrical specifications describe the type of data to be sent over

each wire, the voltage to be used, how signals are to be transmitted over

the wires, as well as protocols for bus arbitration. Some bus standards

are single ended, meaning a single bit of information is read from a

single wire by comparing its voltage to a reference voltage. Any voltage

above the reference is read as a 1, and any voltage below the reference

is read as a 0.

Other buses use differential signaling where a single bit of informa-

tion is read from two wires by comparing their voltages. Whichever of

the two wires has the higher voltage determines whether the bit is read

as a 1 or a 0. Differential buses allow faster switching because they are

less vulnerable to electrical noise. If interference changes the voltage of

a single-ended signal, it may be read as the wrong value. Interference

does not affect differential signals as long as each pair of wires is affected

equally, since all that matters is the difference between the two wires,

not their absolute voltages.

For point-to-point bus standards that only allow transmission of data

in one direction, there is only one chip that will ever drive signals onto

a particular wire. For standards that allow transmission in both direc-

tions or multidrop buses, there are multiple chips that might need to

transmit on the same wire. In these cases, there must be some way of

determining, which is allowed to use the bus next. This protocol is called

bus arbitration.

Arbitration schemes can treat all users of the bus equally or give

some higher priority access than others. Efficient arbitration protocols

are critical to performance since any time spent deciding who will trans-

mit data next is time that no one is transmitting. The problem is greatly

simplified and performance improved by having only one transmitter on

each wire, but this requires a great many more wires to allow all the

needed communication.

All modern computer buses are synchronous buses that use a clock

signal to synchronize the transmission of data over the bus. Chips trans-

mitting or receiving data from the bus use the clock signal to determine

when to send or capture data. Many standards allow one transfer of data

every clock cycle; others allow a transfer only every other cycle, or some-

times two or even four transfers in a single cycle. Buses allowing two

transfers per cycle are called double-pumped, and buses allowing four

transfers per cycle are called quad-pumped. More transfers per cycle

allows for better performance, but makes sending and capturing data

at the proper time much more difficult.

The most important measure of the performance of a bus standard is

its bandwidth. This is specified as the number of data transfers per

second or as the number of bytes of data transmitted per second.

Increasing bandwidth usually means either supporting a wider bus

with more physical wires, increasing the bus clock rate, or allowing

more transfers per cycle.

When we buy a computer it is often marketed as having a particular

frequency, a 3-GHz PC, for example. The clock frequency advertised is

typically that of the microprocessor, arguably the most important, but

by no means the only clock signal inside your computer. Because each

bus standard will specify its own clock frequency, a single computer can

easily have 10 or more separate clock signals.

The processor clock frequency helps determine how quickly the

processor performs calculations, but the clock signal used internally by

the processor is typically higher frequency than any of the bus clocks.

The frequency of the different bus clocks will help determine how quickly

data moves between the different computer components. It is possible

for a computer with a slower processor clock to outperform a computer

with a faster processor clock if it uses higher performance buses.

There is no perfect bus standard. Trade-offs must be made between

performance, cost, and complexity in choosing all the physical and elec-

trical standards; the type of components being connected will have a

large impact on which trade-offs make the most sense. As a result, there

are literally dozens of bus standards and more appearing all the time.

Each one faces the same dilemma that very few manufacturers will

commit to building hardware supporting a new bus standard without

significant demand, but demand is never significant until after some

hardware support is already available.

Despite these difficulties, the appearance of new types of components

and the demand for more performance from existing components steadily

drive the industry to support new bus standards. However, anticipating

which standards will ultimately be successful is extremely difficult, and

it would add significant complexity and risk to the microprocessor design

to try and support all these standards directly. This has led to the creation

of chipsets that support the different bus standards of the computer, so that

the processor doesn’t have to.

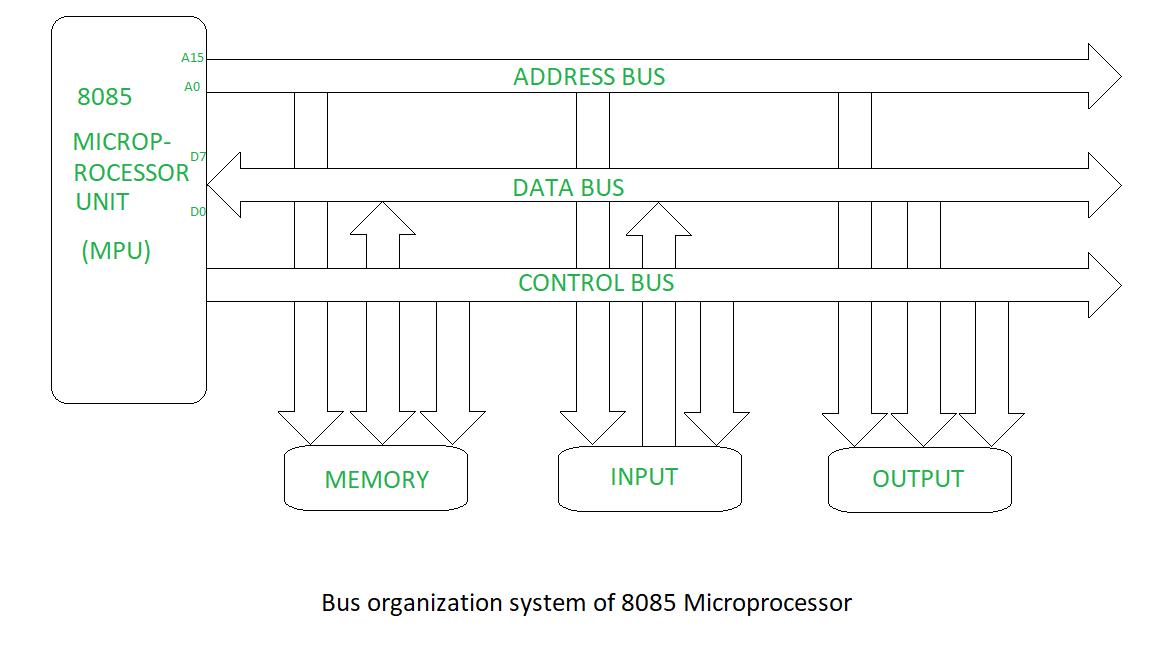

Bus organization of 8085 microprocessor

Bus is a group of conducting wires which carries information, all the peripherals are connected to microprocessor through Bus.

Diagram to represent bus organization system of 8085 Microprocessor.

There are three types of buses.

- Address bus –

It is a group of conducting wires which carries address only.Address bus is unidirectional because data flow in one direction, from microprocessor to memory or from microprocessor to Input/output devices (That is, Out of Microprocessor). Length of Address Bus of 8085 microprocessor is 16 Bit (That is, Four Hexadecimal Digits), ranging from 0000 H to FFFF H, (H denotes Hexadecimal). The microprocessor 8085 can transfer maximum 16 bit address which means it can address 65, 536 different memory location. The Length of the address bus determines the amount of memory a system can address.Such as a system with a 32-bit address bus can address 2^32 memory locations.If each memory location holds one byte, the addressable memory space is 4 GB.However, the actual amount of memory that can be accessed is usually much less than this theoretical limit due to chipset and motherboard limitations. - Data bus –

It is a group of conducting wires which carries Data only.Data bus is bidirectional because data flow in both directions, from microprocessor to memory or Input/Output devices and from memory or Input/Output devices to microprocessor. Length of Data Bus of 8085 microprocessor is 8 Bit (That is, two Hexadecimal Digits), ranging from 00 H to FF H. (H denotes Hexadecimal). When it is write operation, the processor will put the data (to be written) on the data bus, when it is read operation, the memory controller will get the data from specific memory block and put it into the data bus. The width of the data bus is directly related to the largest number that the bus can carry, such as an 8 bit bus can represent 2 to the power of 8 unique values, this equates to the number 0 to 255.A 16 bit bus can carry 0 to 65535. - Control bus –

It is a group of conducting wires, which is used to generate timing and control signals to control all the associated peripherals, microprocessor uses control bus to process data, that is what to do with selected memory location. Some control signals are:

- Memory read

- Memory write

- I/O read

- I/O Write

- Opcode fetch

If one line of control bus may be the read/write line.If the wire is low (no electricity flowing) then the memory is read, if the wire is high (electricity is flowing) then the memory is written

Extra knowledge

Background and nomenclature

Computer systems generally consist of three main parts: the central processing unit (CPU) that processes data, memory that holds the programs and data to be processed, and I/O (input/output) devices as peripherals that communicate with the outside world. An early computer might contain a hand-wired CPU of vacuum tubes, a magnetic drum for main memory, and a punch tape and printer for reading and writing data respectively. A modern system might have a multi-core CPU, DDR4 SDRAM for memory, a solid-state drive for secondary storage, a graphics card and LCD as a display system, a mouse and keyboard for interaction, and a Wi-Fi connection for networking. In both examples, computer buses of one form or another move data between all of these devices.

In most traditional computer architectures, the CPU and main memory tend to be tightly coupled. A microprocessor conventionally is a single chip which has a number of electrical connections on its pins that can be used to select an “address” in the main memory and another set of pins to read and write the data stored at that location. In most cases, the CPU and memory share signalling characteristics and operate in synchrony. The bus connecting the CPU and memory is one of the defining characteristics of the system, and often referred to simply as the system bus.

It is possible to allow peripherals to communicate with memory in the same fashion, attaching adaptors in the form of expansion cards directly to the system bus. This is commonly accomplished through some sort of standardized electrical connector, several of these forming the expansion bus or local bus. However, as the performance differences between the CPU and peripherals varies widely, some solution is generally needed to ensure that peripherals do not slow overall system performance. Many CPUs feature a second set of pins similar to those for communicating with memory, but able to operate at very different speeds and using different protocols. Others use smart controllers to place the data directly in memory, a concept known as direct memory access. Most modern systems combine both solutions, where appropriate.

As the number of potential peripherals grew, using an expansion card for every peripheral became increasingly untenable. This has led to the introduction of bus systems designed specifically to support multiple peripherals. Common examples are the SATA ports in modern computers, which allow a number of hard drives to be connected without the need for a card. However, these high-performance systems are generally too expensive to implement in low-end devices, like a mouse. This has led to the parallel development of a number of low-performance bus systems for these solutions, the most common example being the standardized Universal Serial Bus (USB). All such examples may be referred to as peripheral buses, although this terminology is not universal.

In modern systems the performance difference between the CPU and main memory has grown so great that increasing amounts of high-speed memory is built directly into the CPU, known as a cache. In such systems, CPUs communicate using high-performance buses that operate at speeds much greater than memory, and communicate with memory using protocols similar to those used solely for peripherals in the past. These system buses are also used to communicate with most (or all) other peripherals, through adaptors, which in turn talk to other peripherals and controllers. Such systems are architecturally more similar to multicomputers, communicating over a bus rather than a network. In these cases, expansion buses are entirely separate and no longer share any architecture with their host CPU (and may in fact support many different CPUs, as is the case with PCI). What would have formerly been a system bus is now often known as a front-side bus.

Given these changes, the classical terms “system”, “expansion” and “peripheral” no longer have the same connotations. Other common categorization systems are based on the bus’s primary role, connecting devices internally or externally, PCI vs. SCSI for instance. However, many common modern bus systems can be used for both; SATA and the associated eSATA are one example of a system that would formerly be described as internal, while certain automotive applications use the primarily external IEEE 1394 in a fashion more similar to a system bus. Other examples, like InfiniBand and I²C were designed from the start to be used both internally and externally.

Internal buses

The internal bus, also known as internal data bus, memory bus, system bus or Front-Side-Bus, connects all the internal components of a computer, such as CPU and memory, to the motherboard. Internal data buses are also referred to as a local bus, because they are intended to connect to local devices. This bus is typically rather quick and is independent of the rest of the computer operations.

External buses

The external bus, or expansion bus, is made up of the electronic pathways that connect the different external devices, such as printer etc., to the computer.

Implementation

Early processors used a wire for each bit of the address width. For example, a 16-bit address bus had 16 physical wires making up the bus. As the buses became wider and lengthier, this approach became expensive in terms of the number of chip pins and board traces. Beginning with the Mostek 4096 DRAM, address multiplexing implemented with multiplexers became common. In a multiplexed address scheme, the address is sent in two equal parts on alternate bus cycles. This halves the number of address bus signals required to connect to the memory. For example, a 32-bit address bus can be implemented by using 16 lines and sending the first half of the memory address, immediately followed by the second half memory address

Accessing an individual byte frequently requires reading or writing the full bus width (a word) at once. In these instances the least significant bits of the address bus may not even be implemented – it is instead the responsibility of the controlling device to isolate the individual byte required from the complete word transmitted. This is the case, for instance, with the VESA Local Bus which lacks the two least significant bits, limiting this bus to aligned 32-bit transfers.

Historically, there were also some examples of computers which were only able to address words.

Bus network

A bus network is a network topology in which nodes are directly connected to a common linear (or branched) half-duplex link called a bus

Function

A host on a bus network is called a Station or workstation. In a bus network, every station will receive all network traffic, and the traffic generated by each station has equal transmission priority.A bus network forms a single network segment and collision domain. In order for nodes to transmit on the same bus simultaneously, they use a media access control technology such as carrier sense multiple access (CSMA) or a bus master.

If any link or segment of the bus is severed, all network transmission ceases due to signal bounce caused by the lack of a terminating resistor.

A bus network is a network topology in which nodes are directly connected to a common linear (or branched) half-duplex link called a bus

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

- Very easy to connect a computer or peripheral to a linear bus.

- Requires less cable length than a star topology resulting in lower costs

- The linear architecture is very simple and reliable

- It works well for small networks

- It is easy to extend by joining cable with connector or repeater

- If one node fails, it will not affect the whole network

Disadvantages

- The entire network shuts down if there is a break in the main cable or one of the T connectors break

- Large amount of packet collisions on the network, which results in high amounts of packet loss

- This topology is slow with many nodes in the network

- It is difficult to isolate any faults on the Network

Chipsets

The chipset provides a vital layer of abstraction for the processor. Instead

of the processor having to keep up with the latest hard drive standards,

graphics cards, or DRAM, it can be designed to interface only with the

chipset. The chipset then has the responsibility of understanding all

the different bus standards to be used by all the computer components.

The chipset acts as a bridge between the different bus standards; modern

chipsets typically contain two chips called the Northbridge and

Southbridge.

The Northbridge communicates with the processor and the compo-

nents requiring the highest bandwidth connections. Because this often

includes main memory, the Northbridge is sometimes called the Memory

Controller Hub (MCH). The connections of a Northbridge typically used

with the Pentium 4 or Athlon XP are shown in Fig. 2-1.

In this configuration, the processor communicates only with the

Northbridge and possibly another processor in a multiprocessor system.

This makes bus logic on the processor as simple as possible and allows

the most flexibility in what components are used with the processor. A

single processor design can be sold for use with multiple different types

of memory as long as chipsets are available to support each type.

Sometimes the Northbridge includes a built-in graphics controller as

well as providing a bus to an optional graphics card. This type of

Northbridge is called a Graphics Memory Controller Hub (GMCH).

Including a graphics controller in the Northbridge reduces costs by

avoiding the need to install a separate card, but it reduces performance

by requiring the system’s main memory to be used to store video images

rather than dedicated memory on the graphics card.

Performance can be improved with the loss of some flexibility by pro-

viding a separate connection from the processor directly to memory.

The Athlon 64 uses this configuration. Building a memory controller

directly into the processor die reduces the overall latency of memory

accesses. All other traffic is routed through a separate bus that connects

to the Northbridge chip. Because it now interacts directly only with the

graphics card, this type of Northbridge is sometimes called a graphics

tunnel (Fig. 2-2).

Whereas a direct bus from processor to memory improves perform-

ance, the processor die itself now determines which memory standards

will be supported. New memory types will require a redesign of the

processor rather than simply a new chipset. In addition, the two sepa-

rate buses to the processor will increase the total number of package pins

needed.

Another tactic for improving performance is increasing the total

memory bandwidth by interleaving memory. By providing two separate

bus interfaces to two groups of memory modules, one module can be read-

ing out data while another is receiving a new address. The total memory

store is divided among the separate modules and the Northbridge com-

bines the data from both memory channels to send to the processor. One

disadvantage of memory interleaving is a more expensive Northbridge

chip to handle the multiple connections. Another downside is that new

memory modules must be added in matching pairs to keep the number

of modules on each channel equal.

Communication with all lower-performance components is routed

through an Input output Controller Hub (ICH), also known as the

Southbridge chip. The Southbridge typically controls communication

between the processor and every peripheral except the graphics card and

main memory (Fig. 2-3). The expansion bus supports circuit boards plugged

directly into the motherboard. Peripheral buses support devices external

to the computer case. Usually a separate storage bus supports access to

hard drives and optical storage drives. To provide low-performance “legacy”

standards such as the keyboard, serial port, and parallel port, many

chipsets use a separate chip called the super I/O chip.

The main reason for dividing the functions of the processor,

Northbridge, Southbridge, and super I/O chips among separate chips is

flexibility. It allows different combinations to provide different func-

tionality. Multiple different Northbridge designs can allow a single

processor to work with different types of graphics and memory. Each

Northbridge may be compatible with multiple Southbridge chips to pro-

vide even more combinations. All of these combinations might still use

the same super I/O design to provide legacy standard support.

In recent years, transistor budgets for microprocessors have increased

to the point where the functionality of the chipset could easily be incor-

porated into the processor. This idea is often referred to as system-on-

a-chip, since it provides a single chip ready to interact with all the

common computer components. This is attractive because it requires less

physical space than a separate processor and chipset and packaging

costs are reduced. However, it makes the processor design dependent

upon the different bus standards it supports.

Supporting multiple standards requires duplicate hardware for each

standard built into the processor or supporting different versions of the

processor design. Because the microprocessor is much more expensive

to design, validate, and manufacture, it is often more efficient to place

these functions which depend upon constantly improving bus standards

on separate chips. As new bus standards become widely used, chipsets

are quickly developed to support them without affecting the design of

the microprocessor. For portable and handheld products where physi-

cal space is at a very high premium, it may be worth giving up the flex-

ibility of a separate chipset in order to reduce the number of chips on the

motherboard, but for desktop computers it seems likely that a separate

chipset is here to stay.